Anyone who has been around wine for very long has heard the term “Brix”. You may see it mentioned on technical sheets or hear it discussed in the context of a vineyard harvest. But what exactly is this mysterious critter?

The term “Brix” – also called Balling – is named after Adolf Ferdinand Wenceslaus Brix (1798 – 1870), a German mathematician, engineer, and director of the Royal Prussian Commission for Measurements. Continuing the work of Karl Balling, Herr Brix developed a table for measuring specific gravity of a solution down to five decimal places (Balling had only gone to three). Specific gravity (or density) can be used to determine the amount of sucrose (sugar) in a liquid solution by measuring the refraction index of the liquid by means of a refractometer, hydrometer, or other device.

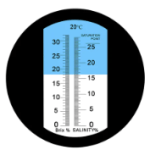

Think about how a stick appears to bend when you submerge half of its length underwater. This is an example of refraction and is the same principle as measuring Brix through a refractometer. Light is bent when it enters a sugary solution such as grape juice. When viewing a liquid through a refractometer, the degree to which it is bent can be used to determine the Brix value.

OK, that’s great you say, but what does this have to do with wine?

In viticulture and oenology, the term “Brix” describes the level of sugar content in grapes, must (grape juices), or finished wine. Growers can use the “degrees Brix” as one of several factors in determining when to harvest. Ideally, a grower (or winemaker) would want the grapes harvested before the sugar content becomes too high. From a winemaker’s perspective, the degrees Brix is an indicator of the potential level of a wine’s alcohol by volume (ABV) once it has been fermented. This can be calculated by multiplying the degrees Brix by 0.59 (note that this value can range anywhere from 0.55 to 0.64 – we won’t go into that here). For example, if grapes are harvested at 24 degrees Brix then the potential ABV will fall somewhere around 14.1% (i.e. 24 x 0.59 = 14.1).

Again, that’s in theory. In practice things are seldom quite that simple. Variations in fermentation temperature, exposure to oxygen, yeast selection, etc., have a direct impact on the fermentation process and can cause the actual ABV to vary.

And let’s not even go down the rabbit hole of how federal laws allow the ABV on the label to vary by as much as 1.5%. We’ll save that for a future post. Cheers!